David A Notes YOUR OFFWORLD INVESTMENTS IN ARTIFICIAL DUMBNESS PAID $? IN DIVIDENDS

Technical communication tactics

Con el tiempo, esos Mapas Desmesurados no satisficieron y los Colegios de Cartógrafos levantaron un Mapa del Imperio, que tenía el tamaño del Imperio y coincidía puntualmente con él. -Del Rigor en la Ciencia, Jorge Luis Borges

In software projects with significant collaboration and coordination dimensions, many problems are ultimately communication problems. Diverse stakeholders can have subtly different mental models of the critical behaviors and constraints, and a wide variety of processes (eg, agile) and tools (eg, requirements and design docs) have been developed to try and help teams converge and align their thinking as quickly and easily as possible.

There is also another important dimension of learning, where the team must discover what the Real Problem and Appropriate Solution actually are, but we’ll set that aside for now and focus on the problem of iterative high-fidelity consensus-building. Note that here I don’t mean “consensus” on the decision-making but rather reaching alignment around the core facts and details, the essential characteristics of the problem and the associated space of solutions.

Maps and territories

A common tactic is to develop an intuition for some domain by considering the most extreme boundary cases. In our software project example, one (admittedly silly) way to ensure everyone has arrived at a common understanding would be for all individuals (or sub teams if you like) to:

- completely build their components out

- try to put it all together at the end

- see if things line up with everyone’s expectations

- if necessary, go back to 1.

In this methodology, the pieces are guaranteed to be highly realistic and detailed expressions of everyone’s thinking, but of course these artifacts are very expensive to produce and even two iterations of this process would not be practical.

At the other end, imagine a workflow where everyone builds out ridiculously low-fidelity versions (say, crayon drawings) of their pieces and then attempts to integrate and evaluate the results. This would be dramatically faster and cheaper, but the elision of any meaningful detail would limit the usefulness of the exercise.

Trying to split the difference, teams could build and share lower-fidelity but still meaningful artifacts like rough prototypes, API specifications, or even simple natural language descriptions. Hopefully, this compromise is able to remedy the excesses of our previous proposals, avoiding the expense of completely building out “the real thing” while still having enough realistic detail to facilitate actual learning on each iteration.

Essential details

…abstraction is what makes precision possible. … Abstraction is really about going to a higher semantic level where we can talk in a language where we can be absolutely precise about the things that we want to be talking about. -Corecursive Podcast: Design Principles From Functional Programming With Rúnar Bjarnason

Working in our “medium-fidelity” regime, how can we make the most of our effort, attention, and communication bandwidth? Possibly we could consider learning from a setting where participants must convey complex and novel ideas under difficult constraints. I am talking, of course, about research papers.

Most of my research paper-reading experience has been around machine learning (ML) papers, which can cover domain-specific problem formulations, mathematical definitions, optimization procedures, systems-oriented implementation details, theoretical guarantees, evaluation criteria, and more. This wide range of content poses challenging trade-offs between precision and brevity, but the diversity of backgrounds in the audience limits the amount of common vocabulary or convention that authors can assume. ML papers therefore give us a nice example of a tricky problem domain for communication and, in some sense, collaboration distributed over space and time. So what tools can we make use of? Let’s walk through a handful of common tactics and specific examples.

Elevator pitch tweet

QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized LLMs (Dettmers et al 2023)

The authors promoted their work with a short and simple post that starts with the headline: “QLoRA: 4-bit finetuning of LLMs.” Follow-up posts begin with a handful of concise and digestible bullet points, such as “97% ChatGPT performance on 1 consumer GPU in 12 hours.” Further down the thread, the author gets into deep dive technical details and surprising quantitative results.

While the initial post acts as a hook or advertisement for the rest of the details, what is great is that, for some use cases, one can stop right there - the core idea is given in (much) fewer than 140 characters. Investing the effort into honing your proposal or idea into such a finely distilled summary can be well worth it.

Block diagrams

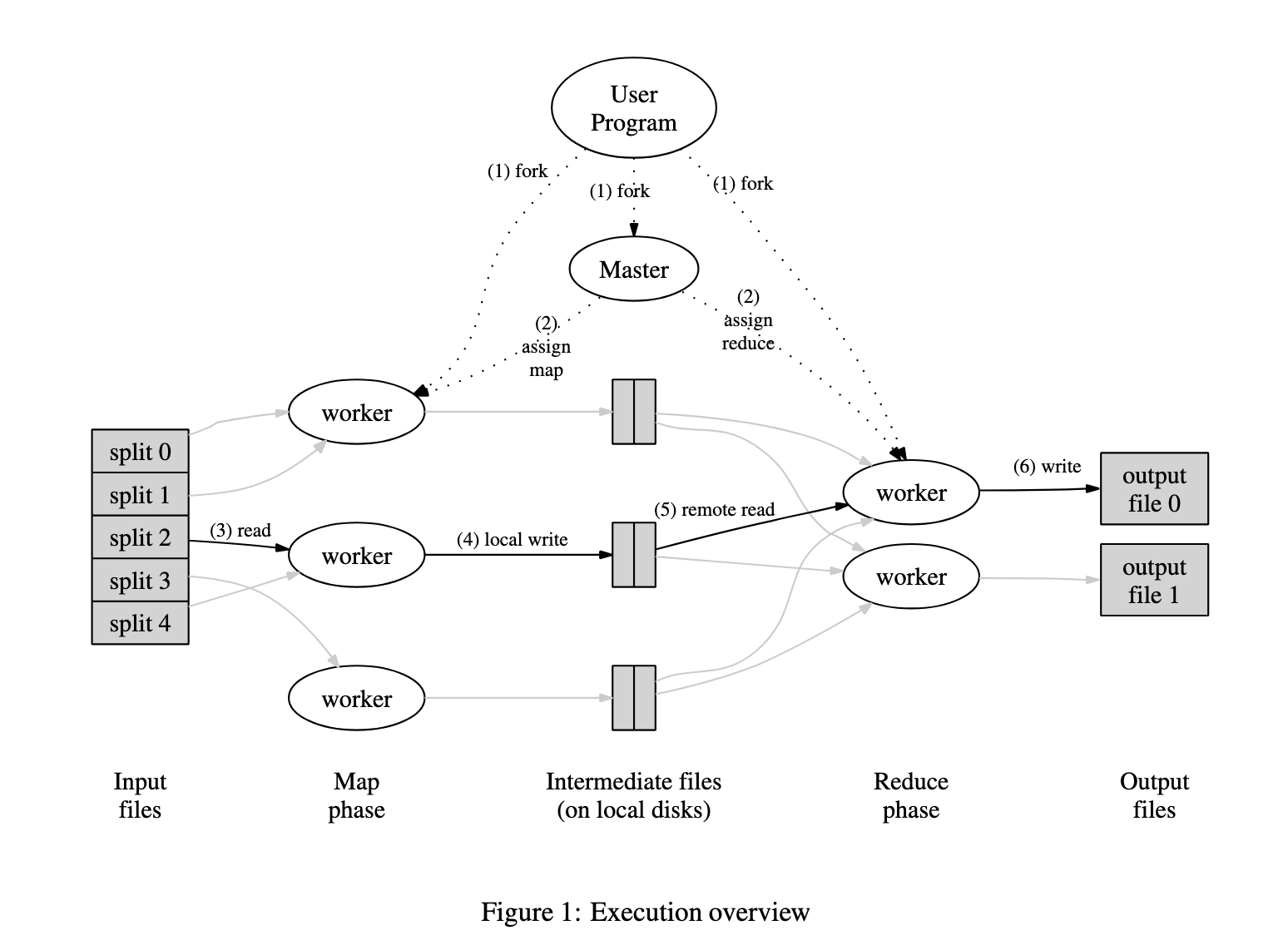

MapReduce: Simplified Data Processing on Large Clusters (Dean & Ghemawat 2004)

“A picture is worth 1000 words” - how does MapReduce work? Take a look:

This diagram captures the essentials:

- what are the major components?

- for each component: what goes in, what comes out?

- which components connect to each other?

Importantly, it also omits details that would only obscure the basic idea:

- how is the networking set up (routers, switches, etc)?

- what formats are the input / output files in?

- what about calculations that require multiple iterations?

Even if there are details that an implementation-minded expert knows and cares about, it is possible to make an intentional decision to leave them out in order to more crisply convey the core idea.

End-to-end examples

Adjusting Machine Learning Decisions for Equal Opportunity and Counterfactual Fairness (Wang, Sridhar & Blei 2023)

Consider automating the admissions process at a university… To illustrate the ideas, we will consider a simple setting. Suppose there are only two attributes for each applicant, their gender and their score on a test… The gender is a protected attribute; the test score is not.

The system proposed in the paper is very general, but is made much clearer with a minimal concrete running example. Even if your system design could handle some very broad range of use cases, walking through one (or a handful) of very specific end-to-end examples can make the mechanics dramatically more comprehensible.

Mathematical formulas

Attention Is All You Need (Vaswani et al 2017)

When appropriately deployed, few human communication technologies can beat mathematical formulas for precision and succinctness. Let’s see the “formula that launched $1T of capex”:

$\mathrm{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \mathrm{softmax}\left(\frac{Q K^\top}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right) V$

An important prerequisite to this guidance is the requirement to first build out the scaffolding in the form of clear supporting definitions. If we don’t know what $Q$ or softmax are, this is not very illuminating. Also, if the subject matter is not a natural fit for this kind of expression, trying to use it anyways can result in an awkward and confusing formulation.

Pseudocode

Stanford CS 221 K Means handout (Chris Piech, based on a handout by Andrew Ng)

In these course notes, the core procedural idea of k-means clustering is made very clear to anyone with the ability to read Python code. Like the MapReduce diagram, inessential detail can be omitted (contributing to the “pseudo” aspect) to simplify and emphasize the main concept. One nice thing on display here is the use of helper functions, as actually inlining the implementations of all the helper functions would have made the main idea less legible.

Show me the code (and results)

End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers (Carion et al 2020)

This is an example of a research paper with an associated repo that provides code, link to the dataset, expected format, and specific commands for training and evaluation.

In general, ML/AI research has raised the bar to include self-contained code artifacts for the core approach and experimental evaluations against benchmark problems and datasets. If there is any doubt or ambiguity about exactly how the idea works or implementation micro-decisions were made, the code provides the ultimate judgment. In other projects, it can be useful to keep this idea of “ground truth” in mind; sometimes there is no substitute for really digging deeply into the details.

Data Science at the Singularity (Donoho 2023) in fact credits the adoption of “frictionless reproducibility” for driving rapid progress in the field of “Empirical Machine Learning.” Note that this doesn’t work without the available datasets and well-defined challenge problems, such as ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (Russakovsky et al 2015).

News you can use

Turning everything into a miniature research paper is probably not a great way to communicate, but this “bag of tricks” can be useful to keep in mind when trying to quickly and effectively convey complex ideas in day-to-day work - good luck!

Written on January 18th, 2026 by David M. Andrzejewski